Arezzo is the perfect city to discover the multilayered strands of history that make Italy so fascinating to explore.

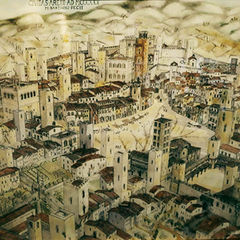

The vibrant history of Arezzo is inextricably connected to its magnificent natural setting in Tuscany, surrounded by fertile valleys, large tracts of old-growth forest, and abundant water supplies. Because of its strategic location along ancient trading routes, Arezzo has prospered from the constant migration of peoples, materials, and ideas as they made their way across the Italian peninsula. Inhabited for more than twenty-five hundred years, Arezzo is the perfect city to discover the multilayered strands of history that make Italy so fascinating to explore.

THE ETRUSCANS

Arezzo's precise founders have been lost to history, and there is no exact record of when Arezzo was settled or by whom. Archeological evidence suggests that the area in and around the modern city of Arezzo was settled around 5000 B.C.E.

Beginning around the eighth century B.C.E., during a period dominated by the Etruscans, a pre-Roman civilization, Arezzo matured into an established urban hub in central Italy, or, as it was known then, Etruria. At its political zenith, Etruscan Arezzo was one of the most important of the twelve city-states that made up the Etruscan Twelve City Confederation.

Early settlers learned the science of viniculture, or grape cultivation, the rituals of warfare, the mechanics of land reclamation and hydraulics, the art of urban planning, the honoring of gods, and excellence in metallurgy. Sometime around the sixth or fifth centuries B.C.E., the Etruscans built up the city of Arezzo on the highest point in the area, to keep watch over the Arno, Tiber and Chiana river valleys below, as well as the areas from which Arezzo drew its wealth.

On what later became St. Donatus Hill, the Etruscans built their acropolis with its important temples, and from this spiritual center the rest of the city spilled down into the lower lying neighborhoods. The modern streets, Fontanella and Pellicceria, are thought to be the original ancient cardo, or main north-south street upon which the early city was loosely laid out, where early inhabitants carried out social, financial, and political activities.

Anthropologists describe Etruscans as highly-cultured, genteel, and extravagant in their personal habits. Women dined with men, party-goers spent months preparing for an important event, and a good fashion sense was key to social mobility. Yet this materialism, according to Roman writers, ultimately contributed to the downfall of the Etruscans in the third century B.C.E. at the hands of the Roman military machine that would eventually rule over the entire Mediterranean basin and beyond.

ROMAN AREZZO

By the second century B.C:E., Arezzo, or Arretium, had evolved into a thriving Roman metropolis, soon to become the third-largest city on the peninsula. Arezzo's key forum was likely located near the modern Piazza Colcitrone. The city also boasted a large second-century amphitheater that held about ten thousand spectators, home to the famous munera, or gladiator events. The foundations of the amphitheater are still visible today, in the grounds of Arezzo's Archaeological Museum.

In the third to first century B.C.E., Arretium became famous for its beautiful red clay pottery, known as Red Coral Ware or Aretine Ware. Scholars have identified three main areas of production within the ancient city walls, with the largest kilns located near the present site of the University of Oklahoma in Arezzo's Kathleen and Francis Rooney Family Residential Learning Center on Via San Domenico. Collectors in the ancient world highly valued the pots for their delicate relief work and fine, coral-like finish. Aretine Ware has been found as far away as India.

By the end of the second century C.E., however, Arretium began to decline in importance. A new trade route, the Via Cassia, connected Rome to Florence, cutting off Arezzo from the Empire's bustling commercial activity. As a result, Hadrian, Rome's architect-emperor, lavished his great building campaigns on Florence rather than on Arretium.

Aretines are rightfully proud of their city's contribution to the intellectual and artistic heritage of Italy. Arezzo's story, while perhaps lesser known than those of Florence or Siena, nevertheless merits its own chapter in understanding Italy's impact of the modern world

EARLY CHRISTIAN AREZZO

The prominence of the early Christian faith in Arezzo is in part due to its second and most famous bishop, Saint Donatus, or San Donato, now the patron saint of the city. Donato was first ordained a deacon and then, upon Bishop Satyrus's death, elevated to the rank of Bishop of Arezzo by Pope Julius I (337 - 352). Through prayer alone, Donatus was said to have miraculously reassembled a Communion chalice shattered by the pagans; astonishingly no wine spilled out during the rest of Communion, and scores of pagans were allegedly converted. A month later, however, a local Roman prefect arrested Donato and had him decapitated sometime in the early years of the second half of the fourth century. Tradition has it that the granite column that sits inside the present cathedral, on the left-hand side aisle, is the actual column upon which Donato was beheaded. His body is enshrined in the cathedral, but his disembodied head is venerated in a beautiful silver and jewel-encrusted reliquary in La Pieve di Santa Maria Assunta on Corso Italia. By connecting San Donato to ancient Rome, early Christianity, and even local traditions, his life becomes an integral part of the larger history of Italy.

THE RISE OF THE ARETINE BISHOPS IN THE MIDDLE AGES

With the Roman Empire in decline, early Christian leaders such as Donato began to wield more power at the local level. A new elite class of citizens - the bishops - began to accumulate the wealth and influence that had once belonged to Etruscan and then Roman elites. The poorly named 'Dark Ages' were, for Arezzo, a time of relative calm and steady prosperity. The monasteries were also highly organized and became points of spiritual and temporal power in cities where political leadership was often weak.

The successful power politics of early bishops helped Arezzo move toward independence sooner than many other communes around it. By 1098, Arezzo declared itself a legal independent commune. The bishops were de facto leaders in both temporal and spiritual spheres.

Between 1052 and 1200, the bishops maintained a council with representatives chosen from the city's four distinct neighborhoods. The members of the council came from a pool of powerful feudal families who owned palaces inside the walls of the city as well as vast tracts of land in the countryside. Wealthy aristocratic families vowed allegiance and military protection to the bishop and he, in turn, protected their local power bases against the rising merchant class. The bishop of Arezzo, therefore, was, for all intents and purposes, a feudal lord and the titular leader of Arezzo - a bishop-count.

Even by medieval standards, Arezzo's financial and political vendettas made for an extremely dangerous place: 40 percent of male citizens died by the age of twenty-five due, in large part, to the violence that ruled the cityscape.

During this volatile period, wealthy families built dozens of 'tower homes'. Rising as high as 260 feet (80 meters), the tower houses functioned as both places of safety and places of business and entertainment. Each tower was a physical representation of its family's local power, competitive vigor, and economic might. These familial class ruled their collective neighborhoods as if they were lords of an independent city. Some neighborhoods were grated and locked in order to maintain tariffs on incoming and outgoing goods. They minted their own coins within the gates, and only certain leaders had the keys to allow inhabitants to come and go freely - a city within a city. A resident of one Arezzo neighborhood might feel out of place, even threatened, when traveling to a neighborhood across town.

THE BATTLE OF CAMPALDINO

A defining historical moment in Arezzo's history took place on June 11, 1289. After a glorious victory over the Sienese army just outside Arezzo in 1288, the Ghibelline forces were in high spirits. Ten thousand soldiers strong, the Ghibellines of Arezzo marched towards their next threat, the Guelfs of Florence, who were marauding in the area. The Arezzo forces were led by Bishop Ubertini, head of the Ghibelline army in the battlefield known as Campaldino. And Campaldino is where he died, along with two thousand other soldiers of the twenty thousand who fought there. It was on this same Campaldino battlefield that a young Italian poet from Florence - Dante Alighieri - fought. The defeat at Campaldino meant that Arezzo would soon fall under the shadow of the bigger and richer Guelf town of Florence. The Battle of Campaldino in fact, laid the foundation for the Florentine dominance in Tuscany.

AREZZO UNDER THE FLORENTINES

Dante once described the Aretines as 'botoli ringhiosi', or growling dogs. The Aretines earned this moniker by revolting against the Florentines six times between 1409 and 1530. Each time the Florentines crushed a rebellion, the Aretines revolted again. Finally, in 1561 under the reign of the Florentine Duke Cosimo I, Arezzo became a truly subject state. Duke Cosimo effectively erased almost a third of the medieval city. In its place, he built a fortress that stands to this day, a visible reminder of the power of the Medici dukes.

In spite of Arezzo's decline, many important intellectuals were born in and around the city during this period. Several studied at the famous cathedral schools and eventually made their way to Florence, Pisa or Rome to pursue their fortunes. The man who contributed most to Arezzo was the prolific artist and writer, Giorgio Vasari (d. 1574). Vasari built the beautiful loggia in Piazza Grande and the altar piece in the Badia church, and transformed the interior of the cathedral into what we see today.

Arezzo's rich twenty-five-hundred-year history is the foundation for the modern, thriving city of one hundred thousand inhabitants today. Aretines are rightfully proud of their city's contribution to the intellectual and artistic heritage of Italy. Arezzo's story, while perhaps lesser known than those of Florence or Siena, nevertheless merits its own chapter in understanding Italy's impact of the modern world.

Adapted from an article by Kirk Duclaux, published in Buon Giorno Arezzo: A Postcard from Tuscany.